New clues and a powerful Wall St. skeptic challenge the official story of CIA financier Nick Deak's brutal murder

By Mark Ames and Alexander Zaitchik On the morning of Nov. 19, 1985, a wild-eyed and disheveled homeless woman entered the reception room at the legendary Wall Street firm of Deak-Perera. Carrying a backpack with an aluminum baseball bat sticking out of the top, her face partially hidden by shocks of greasy, gray-streaked hair falling out from under a wool cap, she demanded to speak with the firm’s 80-year-old founder and president, Nicholas Deak.The 44-year-old drifter’s name was Lois Lang. She had arrived at Port Authority that morning, the final stop on a month-long cross-country Greyhound journey that began in Seattle. Deak-Perera’s receptionist, Frances Lauder, told the woman that Deak was out. Lang became agitated and accused Lauder of lying. Trying to defuse the situation, the receptionist led the unkempt woman down the hallway and showed her Deak’s empty office. “I’ll be in touch,” Lang said, and left for a coffee shop around the corner. From her seat by a window, she kept close watch on 29 Broadway, an art deco skyscraper diagonal from the Bowling Green Bull.

Deak-Perera had been headquartered on the building’s 20th and 21st floors since the late 1960s. Nick Deak, known as “the James Bond of money,” founded the company in 1947 with the financial backing of the CIA. For more than three decades the company had functioned as an unofficial arm of the intelligence agency and was a key asset in the execution of U.S. Cold War foreign policy. From humble beginnings as a spook front and flower import business, the firm grew to become the largest currency and precious metals firm in the Western Hemisphere, if not the world. But on this day in November, the offices were half-empty and employees few. Deak-Perera had been decimated the year before by a federal investigation into its ties to organized crime syndicates from Buenos Aires to Manila. Deak’s former CIA associates did nothing to interfere with the public takedown. Deak-Perera declared bankruptcy in December 1984, setting off panicked and sometimes violent runs on its offices in Latin America and Asia.

Lois Lang had been watching 29 Broadway for two hours when a limousine dropped off Deak and his son Leslie at the building’s revolving-door rear entrance. They took the elevator to the 21st floor, where Lauder informed Deak about the odd visitor. Deak merely shrugged and was settling into his office when he heard a commotion in the reception room. Lang had returned. Frances Lauder let out a fearful “Oh—” shortened by two bangs from a .38 revolver. The first bullet missed. The second struck the secretary between the eyes and exited out the back of her skull.

Deak,

fit and trim at age 80, bounded out of his office. “What was that?” he

shouted. Lang saw him and turned the corner with purpose, aiming the

pistol with both arms. When she had Deak in her sights, she froze,

transfixed. “It was as if she’d finally found what she was looking for,”

a witness later testified. Deak seized the pause to lunge and grab

Lang’s throat with both hands, pressing his body into hers. She fired

once next to Deak’s ear and missed wide, before pushing him away just

enough to bring the gun into his body and land a shot above his heart.

The bullet ricocheted off his collarbone and shredded his organs.

Deak crumbled onto the floor. “Now you’ve got yours,” said Lang. A witness later claimed she took out a camera and snapped photographs of her victim’s expiring body. The bag lady then grabbed the banker by the legs, dragged him into his office, and shut the door.

She emerged shortly and headed for the elevator bank, where three NYPD officers had taken position. They shouted for Lang to freeze. When she reached for her .38, an officer tackled her to the floor. A second cop grabbed her arm as the first hammered her hand with the butt of his gun. As he jarred the revolver free, she turned into a cowering child — “like a frightened animal,” one of the officers later testified.

“Please don’t hurt me,” Lang begged. “He told me I could carry the gun.”

* * *

Lois Lang was tried, convicted and institutionalized under the assumption that she was mad. According to state psychiatrists, she targeted Deak because of random delusions, and her handlers were figments of her cracked imagination. The first judge to hear Lang’s case ruled her unfit for trial and sent her to Kirby Forensic Psychiatric Center. She was sentenced eight years later, in 1993, when a state Supreme Court justice convicted her on two counts of second-degree murder and sent her to the Bedford Hills Correctional Facility upstate, where she remains. Conspiracy was never part of the trial.

Arkadi Kuhlmann has long scoffed at the court’s conclusion. Kuhlmann, then 35 and newly in charge of Deak-Perera’s Canadian operations, became CEO after Deak’s death. Like his Deak-Perera colleagues, he understood that many criminal account holders had lost millions when the firm went bankrupt in 1984. Deak’s subsequent murder, he felt, was no coincidence.

“I never believed that the whole thing was random,” said Kuhlmann, in an interview with Salon. Ditto the government inquiry that triggered the collapse preceding Lang’s rampage. “We were the CIA’s paymaster, and that got to be a little bit embarrassing for them,” he said. “Our time had passed and the usefulness of doing things our way had vanished. The world was changing in the ’80s; you couldn’t just accept bags of cash. Deak was slow at making those changes. And when you lose your sponsorship, you’re out of the game.”

Kuhlmann is the founding CEO of ING Direct, acquired last year by Capital One for $9 billion. It’s a company that sees itself as the banking world’s Southwest Airlines, a cost-cutting upstart with excellent customer service, and its chief executive has a little bit of an outlaw-entrepreneur vibe. He likes to paint and was photographed straddling his customized Harley-Davidson for a 2007 Time magazine profile. If only the magazine had known that his other hobbies include researching the global conspiracy he believed is behind the murder of his old friend and boss. “The question is: Who was actually able to put the hit on?” said Kuhlmann.

Following Deak’s death, Kuhlmann hired a team of private investigators to answer that question. “We went through all the records trying to figure out what happened,” he said. “Deak had assets stuffed away all over the place — in Israel, Macau, Monte Carlo, upstate New York, Hawaii, Saipan.” According to former Deak executives, the company was compartmentalized in a way that only the CEO fully understood, which made efforts to locate deposits like entering a labyrinth.

“We tried to find if there was a record of Lang having an account, maybe under an alias,” Kuhlmann continued. “Or if there was a romantic angle.”

As Kuhlmann traveled the world trying to repair relationships, trace lost assets and solve the mystery of Deak’s murder, he descended ever deeper into a rabbit hole. One of his stops was in Macau, where Deak’s office manager vanished without a trace after the collapse. Kuhlmann entered the paper-strewn offices to find the manager’s girlfriend sitting at her boyfriend’s old desk. She opened a drawer and pulled out a photo she’d found there: a grainy black-and-white snapshot of Nicholas Deak, lying bleeding on his office floor, just minutes from death. The photo, seemingly taken by Lang, had never been made public. Shortly thereafter, two of Kuhlmann’s investigators reported that Lang had met with two Argentineans in Miami before her bus trip to New York.

Kuhlmann has chronicled everything he knows about Deak’s murder in a file cabinet full of notes for a book with the working title “The Betrayal of Nicholas Deak.” He says that he’s sitting on some of his material until certain implicated individuals have died. But the evidence Kuhlmann is willing to discuss — as well as information newly uncovered by Salon — provides ballast for the doubts of Kuhlmann and others that chance led a crazy woman to whack Nick Deak, once a towering figure on Wall Street and at the CIA.

So if the gods of chance and the demons of the mad did not send a mentally ill homeless woman to murder a giant of Cold War covert ops, who did?

* * *

If Nicholas Deak had never existed, Graham Greene would have tried — and failed — to invent him. Born and raised in Transylvania during the last decade of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Deak received a Ph.D. in economics from the University of Neuchâtel in 1929 and held posts with the Hungarian Trade Institute and London’s Overseas Bank before taking a post in the economics department of the League of Nations shortly before World War II. He fled Europe for the United States in 1939, enlisted as a paratrooper in 1942, and was quickly recruited into the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the wartime precursor to the CIA. Among his first assignments was developing a plan to parachute oil executives disguised as Romanian firefighters into the Balkans to sabotage Axis energy supply lines. (Sadly, it was never implemented.) He spent the final year of the war in Burma, where he recruited locals into guerrilla units to fight the Japanese occupation. Japan’s Burmese commander would surrender his samurai sword to Deak at the end of the war, a memento Deak later kept in his Scarsdale, N.Y., attic.

Following V-Day, Deak was stationed in Hanoi and headed U.S. intelligence operations in French Indochina. He assisted with the supply of weapons to French colonial forces and in dispatches to Washington recommended sending unofficial U.S. “advisers” into combat missions, helping set the course for U.S. involvement in Vietnam. His close colleagues at the OSS included future CIA directors William Casey and William Colby, as well as CIA counterintelligence chief James Jesus Angleton.

Deak was a unique talent at a unique time in American history. With Europe in ruins, the country emerged from the war as a true global power in need of imperial know-how. Within the ranks of the OSS, Deak stood out. The blue-blood Yalies that dominated the agency had little experience in global affairs and even less in global finance. And so they turned to the cosmopolitan half-Jewish foreigner to help move the nascent empire’s money around the strategic chessboard. Soon after the war ended, the American government provided the funds to found Deak and Co., a front that began as a global flower-distribution business in Hilo, Hawaii. It soon evolved into a proper bank with growing legitimate business as a broker of foreign currencies with branch offices all over the world, from Beirut to Buenos Aires. In the days of strict global capital controls, when banking was duller and more predictable, Deak’s firm attracted top talent and ambitious finance mavericks with its reputation as one of the most exciting white shoe firms on Wall Street.

But the company’s most important client was always the CIA. From its founding until the late 1970s, Deak’s firm was a key financial arm of the U.S. intelligence complex. Because it carried out the foreign-currency transactions of private entities, Deak and Co. could keep track of who was spiriting money into and out of which countries.

In 1962, for example, Deak warned the CIA that China was planning to invade India after his company’s Hong Kong branch was swamped with Chinese orders for Indian rupees intended for advance soldiers. Deak’s offices were more than observation posts. His company played a crucial role in executing some of the United States’ most infamous covert ops. In 1953, CIA director Alan Dulles tasked Deak with smuggling $1 million into Iran through his offices in Lebanon and Switzerland. The cash went to the street thugs and opposition groups that helped overthrow Iran’s prime minister, Mohammad Mossadegh, in favor of the U.S.-approved shah. Deak’s network also financed the CIA-assisted coups in Guatemala and the Congo.

Meanwhile, the sunny side of Deak’s business thrived. Its retail foreign currency operation, now reconstituted under new ownership and known to the world as Thomas Cooke, became a staple at airports, its multi-packs of francs and marks symbols of every American family’s European vacation. Deak’s retail precious metals business dominated the market after the legalization of gold sales. After a series of sales and reconstitutions, it is today known as Goldline, a major sponsor of Glenn Beck and subject of a recent fraud settlement.

Sen. Frank Church inflicted the first hit on Deak’s public image in 1975. During the Idaho senator’s famous hearings into CIA black ops, it was revealed that Deak’s Hong Kong branch helped the agency funnel millions in Lockheed bribe money to a Japanese yakuza don, political power broker, and former “Class A” war criminal named Yoshio Kodama. One of the most bizarre details involved a priest-turned-bagman who carried over 20 pounds of cash hidden under baskets of oranges on flights between Hong Kong and Tokyo, where he delivered the cash to Lockheed representatives.

Deak’s firm was not penalized for its role in the scandal — bribing foreign officials wasn’t yet illegal in the U.S. — but the damage to his firm’s image was real. The scandal brought down Japan’s government and governments in Western Europe; it also led to the passage of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, the first serious attempt to criminalize overseas bribery. The damage to Deak’s public image was real. It was also quickly compounded by a subsequent New Republic expose that outlined Deak’s role in the Iran, Guatemala and Congo coups. According to those who worked with him at the time, by the late 1970s Deak understood the CIA had begun to see his high profile — matched with a growing business laundering underworld money — as a liability.

If his name was no longer synonymous with the all-American vacation, Deak emerged during the 1970s as a hero in an emergent libertarian gold-bug subculture. As Doomsday-obsessed gold hoarders built financial bomb shelters in the shadow of stagflation, Deak emerged as among the first proto-Libertarian gurus. A fawning profile in Reason magazine compared Deak to “Midas Mulligan or any other character ever conceived of by Ayn Rand.” A font of public lectures and provocative quotes for journalists, Deak drew admiration from fellow gold-circuit riders Ron Paul and Alan Greenspan. He corresponded with Friedrich Hayek. At one gold conference featuring George Will and Louis Rukeyser, the suave banker with the thick Transylvanian accent drew wild applause when he blamed inflation on “welfare” and declared, “I don’t see why the recipient of welfare should be able to vote, because obviously he can vote for more welfare.” Deak also embraced apartheid-era South Africa. “I love to deal with South Africa,” he once said. “Without the white population, the black people there would be in the same shape as west and east Africa.” The media was enthralled. Time tagged him “the James Bond of Money.” Merv Griffin interviewed him with barely concealed awe.

“Deak was incredibly charismatic, the ultimate old world aristocrat,” said Kuhlmann. “He had this imperial bearing and yet was very charming and equally comfortable with high financiers and arms dealers.”

* * *

As the hard-line conservative movement aligned behind Ronald Reagan, things couldn’t have looked better for Deak. His reactionary mix of Spenglerian pessimism, Social Darwinism and Austrian School economics was coming back into vogue. His buddy Bill Casey was put in charge of Reagan’s CIA with a mandate to resurrect the Old Boys Network. People lined up around the world to buy golden “Deak Coins” stamped with his aquiline mug and the motto “Internationalization of Sound Money.” It should have been the start of a grand second act. But it was not to be.

The House of Deak began its rapid collapse in 1983 when a federal informant accused the firm of laundering hundreds of millions of dollars in Colombian cartel cash. Leading the attack from Treasury was John M. Walker, a first cousin of the vice president, George Herbert Walker Bush, who served as CIA chief under Gerald Ford. Suddenly Deak’s decades-long relationship with Casey meant nothing. The knives were out. One of Deak’s executives, Theana Kastens, remembers dropping by 29 Broadway and seeing a freshman congressman named Chuck Schumer sitting in Deak’s office chair, his feet up on the desk, rifling through papers.

“He felt profoundly betrayed,” said Kastens, whose father, Pennsylvanian Rep. Gus Yatron, served on the House Foreign Affairs Committee during the Iran-Contra hearings. “He was bitter and despondent.”

When Reagan’s Justice Department established a presidential commission to investigate the charges, a furious Deak rejected participation in what he regarded as a show trial. He was summoned to testify in Washington and refused. Finally, on Nov. 29, 1984, the feds dragged him before the cameras under subpoena for a public dressing-down. Deak openly displayed his contempt for the proceedings. Sardonic and aloof, he responded to questions about his company’s Swiss-like policy of accepting all deposits by asserting that it was the job of law enforcement, not Nicholas Deak, to track drug money. His outrage at being singled out was understandable. At the time, CIA director Casey was funding Nicaragua’s contra rebels with the agency’s own cocaine trade profits. Of course, the exact justification for burning Deak didn’t matter. And as with the Church hearings, his company was never actually even prosecuted. The message to Deak and his underworld clients was more important: Deak-Perera had lost its protection and was in the cross hairs.

The fallout was immediate. Deak’s crime-commission appearance triggered a worldwide run on the company’s deposits. Crowds mobbed Deak offices in Argentina and Hong Kong. Millions of dollars in gray and black deposits vanished. Among the jilted clients were Macau Triads and Latin American drug cartels. A retired DEA official who worked in Hong Kong in the 1980s said, “Nick Deak screwed over a lot of people, including the Macau mob.” Philip Bowering, a Hong Kong correspondent for the Far Eastern Economic Review in the 1980s, said there’s no question Deak made a lot of enemies that year. “He crossed one of the Macau mafia,” he said. “But on what issue I have no idea.”

After a bankruptcy declaration in December 1984, Deak tried not to think about his new enemies and focus on sorting through his company’s remains. He spent 1985 traveling the globe with his son Leslie, trying ineffectually to revive the firm. Then one wintry afternoon, with the holidays approaching and the “Miami Vice” theme climbing the Billboard charts, a homeless woman from Seattle named Lang showed up at 29 Broadway and brought Nick Deak’s long and storied run to an end.

* * *

Nothing about Lois Lang’s story ever made much sense. But then, why should anything about a paranoid-schizophrenic bag lady have to make sense? This is the logic that sent Lang to federal prison and satisfied the court. But those closest to the case — including former Deak executives; the prosecuting assistant district attorney; and the daughter of Deak’s secretary, Bonnie Lauder — have never been convinced. “I have always believed,” Lauder told us at her home in Staten Island, “that there was something wrong with the story I was told about how my mother was killed by a random bag lady.”

Lauder is not alone in suspecting deeper forces at work.

“I never bought the operetta story of a crazy woman shooting the elephant hunter point-blank in his own office,” said Antal Fekete, a Canadian economist who met Deak while teaching at Princeton in the 1970s. “I often think that the producers at the CIA should pick a more credible scenario when they plot the elimination of some of their former employees who babble too much.” Otto Roethenmund, a former executive in Deak’s company who was in the office the day of the killing, said Deak’s murder “was a very, let us say, interesting thing. But I prefer not to speculate.”

New revelations about Lois Lang’s transformation from homecoming queen to homeless killer provide excellent grist for substantive speculation, if not the basis for officially reopening the Deak case.

A standout college athlete with an M.A. from the University of Illinois, Lang married in the mid-’60s and took a job coaching the University of California-Santa Barbara women’s tennis and fencing teams. An old U.C.-Santa Barbara yearbook shows coach Lang standing tall in a team photo. It was around this time that she began losing her mind, seeing “fakes” all around her, strangers whom she accused of pretending to be family members, her husband and, at an open-casket funeral, her mother’s corpse.

In 1970, the university declined to renew her coaching contract. Lang and her husband soon divorced. Her life quickly became a blur. Lang complained of “amnesia” and said that her ex-husband’s business partner moved her into an apartment in Mountain View, Calif., where she lived on “grants” and “took flying lessons.” (Moffett Field Naval Base and NASA’s Ames Research Center are located there). She told psychiatrists in 1985 that this business partner, or his “fakes,” took her to Deak’s offices at 29 Broadway in 1971. She said that “friends” taught her marksmanship at firing ranges. In August 1975, records show that Lang was discovered naked and catatonic in a Santa Clara motel room. (Neither Lang’s ex-husband nor his “business partner” could be located. Lang, who is imprisoned at a federal facility two hours north of New York City, did not respond to interview requests.)

Police responding to the motel room took Lang to nearby Santa Clara Valley Medical Center. For the next month, she was put under the care of Dr. Frederick Melges, a psychiatrist associated with the Stanford Research Institute. One of Dr. Melges’ main areas of research: drug-aided hypnosis. A few years after Lang was put in Melges’ care, the New York Times exposed the Stanford Research Institute as a center for CIA research into “brain-washing” and “mind-control” experiments in which unwitting subjects were dosed with hallucinogenic drugs and subjected to hypnosis. Melges, who died in 1988, is today remembered in the field for his research on the relationship between perceptions of time and mental illness.

Congressional hearings subsequently uncovered a large network of top-secret CIA-funded psychological warfare programs grouped loosely under the project name MK-ULTRA. These programs today sound like absurd cloak-and-dagger relics of “Twilight Zone”-inflected Cold War hysteria. But the people running these programs, which continued until at least 1979, were often leading researchers backed by the U.S. government. Enormous resources were committed to the study of how human behavior might be controlled for the purpose of interrogation and the creation of “programmed” assassins and couriers. In a detailed roundup of MK-ULRA-related operations, Psychology Today explained that the CIA “conducted or sponsored at least 419 secret drug-testing projects” at “86 United States and Canadian hospitals, prisons, universities, and military installations,” and that “by the agency’s own admission, many [experimental subjects] were ‘unwitting’.”

The Stanford Research Institute received CIA funding, and Dr. Melges published work about using drugs and hypnosis to create “disassociative states,” i.e., induced schizophrenia. One of Melges’ partners on these experiments was a doctor named Leo E. Hollister, who first dosed Ken Kesey with LSD as part of an Army experiment in 1960. He later admitted to author John Marks that he conducted drug research for the CIA. Marks’ 1979 book, “The Search for the Manchurian Candidate,” contains numerous such revelations about other government researchers.

In other words, the doctor who cared for Lang in Santa Clara was a senior figure at one of the CIA’s top institutional grantees. He worked side-by-side with a self-identified CIA collaborator, and conducted research into the kind of drug-induced behavior modification that the agency is known to have funded.

Following her release from Melges’ care, Lang began a long period as a drifter, leaving behind a record typical of such a life: petty crimes, arrests, stints in and out of psychiatric hospitals. Her only known job was at the once famously mobbed-up Harrah’s casino on the Nevada-California border (where Frank Sinatra’s son was kidnapped in 1963). By the early 1980s, Lang drifted north to her birthplace and spent her last free years lurking around the University of Washington campus wearing a feathered Robin Hood cap. Occasionally she was arrested and sent to one of the nearby mental hospitals before making her way back again. A local police officer told the New York Times after her arrest in 1985 that Lang “usually had money,” despite roaming “the [university] campus in unkempt clothes, usually wearing a green felt Tyrolean-style hat.” Once the police found more than $800 in her possession.

As with Stanford, the university employed a military-linked behavioral psychiatrist, Dr. Donald Dudley, who later became infamous for carrying out experiments in behavior modification. Dudley taught there from the 1960s through the early 1990s, and also worked at nearby mental institutions where Lang was periodically committed. The landmark lawsuit that ended Dudley’s career revealed that Dudley’s hobby was taking patients brought to him for lesser mental illnesses, pumping them full of drugs, hypnotizing them, and trying to turn them into killers.

We know this thanks to a suit brought by the family of Stephen Drummond, who entered Dudley’s care in 1989 for autism treatment. He was returned to his family in 1992 suffering from severe catatonia. According to lawsuit testimony, Dudley shot Drummond up with sodium amytal and hypnotized him with the intention of “erasing” a portion of his brain and turning him into an assassin. When Drummond’s mother confronted Dudley, the mad scientist threatened to have her killed, claiming he worked for the CIA. Dudley was arrested soon after the confrontation in a local hotel where he had shacked up to “treat” a suicidal 15-year-old drifter. Dudley had given the boy sodium amytal and several other drugs, hypnotized him, and convinced him that he was part of a secret army of assassins. Police were called in when the boy threatened hotel staff with a .44 caliber handgun. Not long after, Dudley died in state custody and his estate was forced to pay the largest psychotherapy negligence lawsuit in history. During the trial, it emerged that Dudley had possibly subjected hundreds of victims to similar experiments. Lang was not mentioned.

* * *

If Lang was tapped to whack Nicholas Deak, she was part of a long tradition. In mobster literature, insane assassins are regular characters. “Nuts were used from time to time by certain people for certain matters,” explains Jimmy Hoffa’s former right-hand man, Frank “The Irishman” Sheeran, in his memoir, “I Heard You Paint Houses.” Chuck Giancana, brother of Chicago mob boss Sam Giancana, writes that he once heard his brother say that “picking a nutcase who was also a sharpshooter” to carry out an assassination was “as old as the Sicilian hills.”

An untraceable hit is the best hit, and the mind of a “nut” is all but untraceable. Hoffa associate Sheeran identified two high-profile examples in America. One took place during Hoffa’s trial in Nashville in 1962, when, during a break in the trial, a young paranoid-schizophrenic named William Swanson rushed into the courthouse and began firing at Hoffa. Hoffa’s attacker had been released from a California mental institution a few months before coming out to Nashville. “I had been struggling with something in me that told me I had to kill someone for over a year, but I didn’t know who,” Swanson told police after he was arrested. “Then a voice told me, ‘You have to kill Hoffa’ — it said it twice.” Hoffa had always assumed that rival mobsters had trained Swanson to take him out. A few years later, in 1971, New York’s top Mafia don, Joseph Colombo, was gunned down at an Italian-American pride rally by a 24-year-old African-American paranoid-schizophrenic, who was killed seconds later by someone in the crowd.

The Colombo assassination made headlines for months, and although everyone from the police chief down assumed mob involvement, the hit was never solved. Assassin Jerome Johnson was a black neo-Nazi as well as a practiced marksman and member of the NRA. He also thought he was God. The night before murdering Colombo, he arrived by bus from Cambridge, Mass., carrying a caged monkey. No one ever figured out whom Johnson visited in Cambridge, how he got his money, or why he had the monkey.

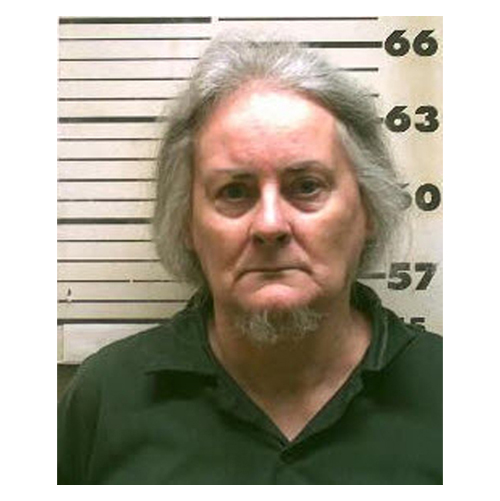

Lois Lang spoke to police and doctors on the day of her own arrival by bus. As during subsequent interviews with psychiatrists, she was incapable of offering more than sketchy and incoherent autobiographical information. She was hospitalized for eight years before a judge finally declared her fit to stand trial in 1993. The prosecution team found the case very odd — the D.A. reportedly still thinks about it — but didn’t spend much time delving into the motivations of the madwoman. Lang has been in Bedford Hills federal prison ever since. Her longtime attorney is deceased. She has grown a beard like a billy goat and ignores all interview requests. Her most recent parole interview was last August. Like every previous date, she failed to attend.

* * *

If the tossed-off human byproduct of a half-baked CIA assassin program was indeed recruited by one of many potential-suspect crime syndicates to kill Deak, how did it go down? Who provided Lang’s name to whom? Who helped her to buy a bus ticket to Florida via Tijuana? Who helped her buy a Saturday Night Special in Orlando and taught her to shoot?

Some of those loose ends may be tied up by opening government files. Since the 1980s, the CIA and Department of Defense have had to reveal thousands of pages of documents and settle scores of lawsuits filed by victims of various mind-control experiments. Recently a major class-action lawsuit was filed on behalf of over 7,000 veterans subjected to chemical and biological experiments at the 11th Circuit federal courts.

Arkadi Kuhlmann, the ING Direct CEO, may hold a few important leads. During our conversation, we told Kuhlmann that Lang was hospitalized under the supervision of at least one doctor with a documented interest in drug-induced hypnosis. He wasn’t at all surprised. “How does a woman like her actually handle a gun and get off two clean shots?” he asks. “That’s execution-style. It’s hard to function like an executioner one minute, but be loose around the edges. Unless you’re brainwashed like a robot.”

He then divulged a discovery he has kept to himself for nearly three decades. In Macau, Kuhlmann said, one of his investigators was tipped off about the potential involvement of two Argentinean gangsters in Deak’s killing. His team was able to trace the men’s movements in the months before the murders and discovered they had met with Lois Lang in Miami, not far from where Lang bought her murder weapon and took the bus to New York. “We’re absolutely certain they met with Lang,” Kuhlmann said.

What was this duo’s precise connection to Deak? And how did they come to meet Lois Lang?

Here Kuhlmann pauses for the first time.

“I know a few more things about them,” he said. “But this gets a little dicey. I don’t know how to play that game. I don’t want to be the next target.”

* * *

So let’s imagine that Lang was a product of a government-connected mind-control program. If jilted gangsters from Argentina and Macau used her to exact revenge, what could possibly connect them?

Allow us one more speculation rooted in the record.

As Deak’s banking empire was collapsing in December 1984, the depositors in Deak’s “non-bank” banking outfits — specifically the Connecticut-based Deak-Perera Wall Street and Deak-Perera International Banking Corporation — included numerous rich and shady Argentineans parking their “black” cash outside of Argentina. The country was in upheaval following the Falklands War debacle that led to the overthrow of Argentina’s quasi-fascist junta and the restoration of democracy. For decades, Argentina had been Latin America’s haven for some of the world’s most wanted, its capital city of Buenos Aires a European-flavored nexus for Nazi war criminals, global Mafiosi and Western spy services. The 1970s were the scene’s heyday, when Argentina’s junta coordinated “Operation Condor,” a regional crackdown carried out with the support of the CIA and allied dictatorships. Condor resulted in the deaths of tens of thousands of suspected leftists, including the car bombing in Washington, D.C., of Chile’s former ambassador.

This coziness continued into the early 1980s. Upon Reagan’s election, one of the first things Bill Casey did was farm out Argentina’s death squad commanders as trainers and commanders of anti-Sandinista death squads in Nicaragua, known as the contras. This arrangement worked fine until mid-1982, when Britain went to war with Argentina over the Falklands, and Reagan sided with Thatcher. In the wake of the war, the Argentine junta-mafia power structure collapsed. Suddenly a lot of very scary Argentineans with ties to the underworld and the CIA began to move their money safely out of Argentina, where Deak maintained a large foreign currency exchange business.

It’s all but certain that the bankruptcy of Nicholas Deak resulted in the burning of some of the CIA’s most ruthless, bloodstained allies of the Cold War. With his CIA ties and right-wing politics, Deak knew many of them personally. Kuhlmann recounted to us how shortly after he joined the firm, Deak brought him to a meeting with one of Chilean Gen. Augusto Pinochet’s top arms dealers. Such relationships combining financial and political networks offer a plausible scenario for how Deak’s bilked banking clients might have been able to tap a possible victim of CIA behavior modification experiments like Lois Lang. If any capital flight demographic in 1984 had deep ties to the CIA and their experts in torture, interrogation techniques and related “science,” it was Argentina’s fleeing junta-elite.

“Lang and the Argentineans — it’s like a jigsaw puzzle,” said Kuhlmann with a sigh. “You have to fill in the missing 30 percent. That doesn’t work in a court of law.”

Continue Reading

CloseDeak crumbled onto the floor. “Now you’ve got yours,” said Lang. A witness later claimed she took out a camera and snapped photographs of her victim’s expiring body. The bag lady then grabbed the banker by the legs, dragged him into his office, and shut the door.

She emerged shortly and headed for the elevator bank, where three NYPD officers had taken position. They shouted for Lang to freeze. When she reached for her .38, an officer tackled her to the floor. A second cop grabbed her arm as the first hammered her hand with the butt of his gun. As he jarred the revolver free, she turned into a cowering child — “like a frightened animal,” one of the officers later testified.

“Please don’t hurt me,” Lang begged. “He told me I could carry the gun.”

* * *

Lois Lang was tried, convicted and institutionalized under the assumption that she was mad. According to state psychiatrists, she targeted Deak because of random delusions, and her handlers were figments of her cracked imagination. The first judge to hear Lang’s case ruled her unfit for trial and sent her to Kirby Forensic Psychiatric Center. She was sentenced eight years later, in 1993, when a state Supreme Court justice convicted her on two counts of second-degree murder and sent her to the Bedford Hills Correctional Facility upstate, where she remains. Conspiracy was never part of the trial.

Arkadi Kuhlmann has long scoffed at the court’s conclusion. Kuhlmann, then 35 and newly in charge of Deak-Perera’s Canadian operations, became CEO after Deak’s death. Like his Deak-Perera colleagues, he understood that many criminal account holders had lost millions when the firm went bankrupt in 1984. Deak’s subsequent murder, he felt, was no coincidence.

“I never believed that the whole thing was random,” said Kuhlmann, in an interview with Salon. Ditto the government inquiry that triggered the collapse preceding Lang’s rampage. “We were the CIA’s paymaster, and that got to be a little bit embarrassing for them,” he said. “Our time had passed and the usefulness of doing things our way had vanished. The world was changing in the ’80s; you couldn’t just accept bags of cash. Deak was slow at making those changes. And when you lose your sponsorship, you’re out of the game.”

Kuhlmann is the founding CEO of ING Direct, acquired last year by Capital One for $9 billion. It’s a company that sees itself as the banking world’s Southwest Airlines, a cost-cutting upstart with excellent customer service, and its chief executive has a little bit of an outlaw-entrepreneur vibe. He likes to paint and was photographed straddling his customized Harley-Davidson for a 2007 Time magazine profile. If only the magazine had known that his other hobbies include researching the global conspiracy he believed is behind the murder of his old friend and boss. “The question is: Who was actually able to put the hit on?” said Kuhlmann.

Following Deak’s death, Kuhlmann hired a team of private investigators to answer that question. “We went through all the records trying to figure out what happened,” he said. “Deak had assets stuffed away all over the place — in Israel, Macau, Monte Carlo, upstate New York, Hawaii, Saipan.” According to former Deak executives, the company was compartmentalized in a way that only the CEO fully understood, which made efforts to locate deposits like entering a labyrinth.

“We tried to find if there was a record of Lang having an account, maybe under an alias,” Kuhlmann continued. “Or if there was a romantic angle.”

As Kuhlmann traveled the world trying to repair relationships, trace lost assets and solve the mystery of Deak’s murder, he descended ever deeper into a rabbit hole. One of his stops was in Macau, where Deak’s office manager vanished without a trace after the collapse. Kuhlmann entered the paper-strewn offices to find the manager’s girlfriend sitting at her boyfriend’s old desk. She opened a drawer and pulled out a photo she’d found there: a grainy black-and-white snapshot of Nicholas Deak, lying bleeding on his office floor, just minutes from death. The photo, seemingly taken by Lang, had never been made public. Shortly thereafter, two of Kuhlmann’s investigators reported that Lang had met with two Argentineans in Miami before her bus trip to New York.

Kuhlmann has chronicled everything he knows about Deak’s murder in a file cabinet full of notes for a book with the working title “The Betrayal of Nicholas Deak.” He says that he’s sitting on some of his material until certain implicated individuals have died. But the evidence Kuhlmann is willing to discuss — as well as information newly uncovered by Salon — provides ballast for the doubts of Kuhlmann and others that chance led a crazy woman to whack Nick Deak, once a towering figure on Wall Street and at the CIA.

So if the gods of chance and the demons of the mad did not send a mentally ill homeless woman to murder a giant of Cold War covert ops, who did?

* * *

If Nicholas Deak had never existed, Graham Greene would have tried — and failed — to invent him. Born and raised in Transylvania during the last decade of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Deak received a Ph.D. in economics from the University of Neuchâtel in 1929 and held posts with the Hungarian Trade Institute and London’s Overseas Bank before taking a post in the economics department of the League of Nations shortly before World War II. He fled Europe for the United States in 1939, enlisted as a paratrooper in 1942, and was quickly recruited into the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the wartime precursor to the CIA. Among his first assignments was developing a plan to parachute oil executives disguised as Romanian firefighters into the Balkans to sabotage Axis energy supply lines. (Sadly, it was never implemented.) He spent the final year of the war in Burma, where he recruited locals into guerrilla units to fight the Japanese occupation. Japan’s Burmese commander would surrender his samurai sword to Deak at the end of the war, a memento Deak later kept in his Scarsdale, N.Y., attic.

Following V-Day, Deak was stationed in Hanoi and headed U.S. intelligence operations in French Indochina. He assisted with the supply of weapons to French colonial forces and in dispatches to Washington recommended sending unofficial U.S. “advisers” into combat missions, helping set the course for U.S. involvement in Vietnam. His close colleagues at the OSS included future CIA directors William Casey and William Colby, as well as CIA counterintelligence chief James Jesus Angleton.

Deak was a unique talent at a unique time in American history. With Europe in ruins, the country emerged from the war as a true global power in need of imperial know-how. Within the ranks of the OSS, Deak stood out. The blue-blood Yalies that dominated the agency had little experience in global affairs and even less in global finance. And so they turned to the cosmopolitan half-Jewish foreigner to help move the nascent empire’s money around the strategic chessboard. Soon after the war ended, the American government provided the funds to found Deak and Co., a front that began as a global flower-distribution business in Hilo, Hawaii. It soon evolved into a proper bank with growing legitimate business as a broker of foreign currencies with branch offices all over the world, from Beirut to Buenos Aires. In the days of strict global capital controls, when banking was duller and more predictable, Deak’s firm attracted top talent and ambitious finance mavericks with its reputation as one of the most exciting white shoe firms on Wall Street.

But the company’s most important client was always the CIA. From its founding until the late 1970s, Deak’s firm was a key financial arm of the U.S. intelligence complex. Because it carried out the foreign-currency transactions of private entities, Deak and Co. could keep track of who was spiriting money into and out of which countries.

In 1962, for example, Deak warned the CIA that China was planning to invade India after his company’s Hong Kong branch was swamped with Chinese orders for Indian rupees intended for advance soldiers. Deak’s offices were more than observation posts. His company played a crucial role in executing some of the United States’ most infamous covert ops. In 1953, CIA director Alan Dulles tasked Deak with smuggling $1 million into Iran through his offices in Lebanon and Switzerland. The cash went to the street thugs and opposition groups that helped overthrow Iran’s prime minister, Mohammad Mossadegh, in favor of the U.S.-approved shah. Deak’s network also financed the CIA-assisted coups in Guatemala and the Congo.

Meanwhile, the sunny side of Deak’s business thrived. Its retail foreign currency operation, now reconstituted under new ownership and known to the world as Thomas Cooke, became a staple at airports, its multi-packs of francs and marks symbols of every American family’s European vacation. Deak’s retail precious metals business dominated the market after the legalization of gold sales. After a series of sales and reconstitutions, it is today known as Goldline, a major sponsor of Glenn Beck and subject of a recent fraud settlement.

Sen. Frank Church inflicted the first hit on Deak’s public image in 1975. During the Idaho senator’s famous hearings into CIA black ops, it was revealed that Deak’s Hong Kong branch helped the agency funnel millions in Lockheed bribe money to a Japanese yakuza don, political power broker, and former “Class A” war criminal named Yoshio Kodama. One of the most bizarre details involved a priest-turned-bagman who carried over 20 pounds of cash hidden under baskets of oranges on flights between Hong Kong and Tokyo, where he delivered the cash to Lockheed representatives.

Deak’s firm was not penalized for its role in the scandal — bribing foreign officials wasn’t yet illegal in the U.S. — but the damage to his firm’s image was real. The scandal brought down Japan’s government and governments in Western Europe; it also led to the passage of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, the first serious attempt to criminalize overseas bribery. The damage to Deak’s public image was real. It was also quickly compounded by a subsequent New Republic expose that outlined Deak’s role in the Iran, Guatemala and Congo coups. According to those who worked with him at the time, by the late 1970s Deak understood the CIA had begun to see his high profile — matched with a growing business laundering underworld money — as a liability.

If his name was no longer synonymous with the all-American vacation, Deak emerged during the 1970s as a hero in an emergent libertarian gold-bug subculture. As Doomsday-obsessed gold hoarders built financial bomb shelters in the shadow of stagflation, Deak emerged as among the first proto-Libertarian gurus. A fawning profile in Reason magazine compared Deak to “Midas Mulligan or any other character ever conceived of by Ayn Rand.” A font of public lectures and provocative quotes for journalists, Deak drew admiration from fellow gold-circuit riders Ron Paul and Alan Greenspan. He corresponded with Friedrich Hayek. At one gold conference featuring George Will and Louis Rukeyser, the suave banker with the thick Transylvanian accent drew wild applause when he blamed inflation on “welfare” and declared, “I don’t see why the recipient of welfare should be able to vote, because obviously he can vote for more welfare.” Deak also embraced apartheid-era South Africa. “I love to deal with South Africa,” he once said. “Without the white population, the black people there would be in the same shape as west and east Africa.” The media was enthralled. Time tagged him “the James Bond of Money.” Merv Griffin interviewed him with barely concealed awe.

“Deak was incredibly charismatic, the ultimate old world aristocrat,” said Kuhlmann. “He had this imperial bearing and yet was very charming and equally comfortable with high financiers and arms dealers.”

* * *

As the hard-line conservative movement aligned behind Ronald Reagan, things couldn’t have looked better for Deak. His reactionary mix of Spenglerian pessimism, Social Darwinism and Austrian School economics was coming back into vogue. His buddy Bill Casey was put in charge of Reagan’s CIA with a mandate to resurrect the Old Boys Network. People lined up around the world to buy golden “Deak Coins” stamped with his aquiline mug and the motto “Internationalization of Sound Money.” It should have been the start of a grand second act. But it was not to be.

The House of Deak began its rapid collapse in 1983 when a federal informant accused the firm of laundering hundreds of millions of dollars in Colombian cartel cash. Leading the attack from Treasury was John M. Walker, a first cousin of the vice president, George Herbert Walker Bush, who served as CIA chief under Gerald Ford. Suddenly Deak’s decades-long relationship with Casey meant nothing. The knives were out. One of Deak’s executives, Theana Kastens, remembers dropping by 29 Broadway and seeing a freshman congressman named Chuck Schumer sitting in Deak’s office chair, his feet up on the desk, rifling through papers.

“He felt profoundly betrayed,” said Kastens, whose father, Pennsylvanian Rep. Gus Yatron, served on the House Foreign Affairs Committee during the Iran-Contra hearings. “He was bitter and despondent.”

When Reagan’s Justice Department established a presidential commission to investigate the charges, a furious Deak rejected participation in what he regarded as a show trial. He was summoned to testify in Washington and refused. Finally, on Nov. 29, 1984, the feds dragged him before the cameras under subpoena for a public dressing-down. Deak openly displayed his contempt for the proceedings. Sardonic and aloof, he responded to questions about his company’s Swiss-like policy of accepting all deposits by asserting that it was the job of law enforcement, not Nicholas Deak, to track drug money. His outrage at being singled out was understandable. At the time, CIA director Casey was funding Nicaragua’s contra rebels with the agency’s own cocaine trade profits. Of course, the exact justification for burning Deak didn’t matter. And as with the Church hearings, his company was never actually even prosecuted. The message to Deak and his underworld clients was more important: Deak-Perera had lost its protection and was in the cross hairs.

The fallout was immediate. Deak’s crime-commission appearance triggered a worldwide run on the company’s deposits. Crowds mobbed Deak offices in Argentina and Hong Kong. Millions of dollars in gray and black deposits vanished. Among the jilted clients were Macau Triads and Latin American drug cartels. A retired DEA official who worked in Hong Kong in the 1980s said, “Nick Deak screwed over a lot of people, including the Macau mob.” Philip Bowering, a Hong Kong correspondent for the Far Eastern Economic Review in the 1980s, said there’s no question Deak made a lot of enemies that year. “He crossed one of the Macau mafia,” he said. “But on what issue I have no idea.”

After a bankruptcy declaration in December 1984, Deak tried not to think about his new enemies and focus on sorting through his company’s remains. He spent 1985 traveling the globe with his son Leslie, trying ineffectually to revive the firm. Then one wintry afternoon, with the holidays approaching and the “Miami Vice” theme climbing the Billboard charts, a homeless woman from Seattle named Lang showed up at 29 Broadway and brought Nick Deak’s long and storied run to an end.

* * *

Nothing about Lois Lang’s story ever made much sense. But then, why should anything about a paranoid-schizophrenic bag lady have to make sense? This is the logic that sent Lang to federal prison and satisfied the court. But those closest to the case — including former Deak executives; the prosecuting assistant district attorney; and the daughter of Deak’s secretary, Bonnie Lauder — have never been convinced. “I have always believed,” Lauder told us at her home in Staten Island, “that there was something wrong with the story I was told about how my mother was killed by a random bag lady.”

Lauder is not alone in suspecting deeper forces at work.

“I never bought the operetta story of a crazy woman shooting the elephant hunter point-blank in his own office,” said Antal Fekete, a Canadian economist who met Deak while teaching at Princeton in the 1970s. “I often think that the producers at the CIA should pick a more credible scenario when they plot the elimination of some of their former employees who babble too much.” Otto Roethenmund, a former executive in Deak’s company who was in the office the day of the killing, said Deak’s murder “was a very, let us say, interesting thing. But I prefer not to speculate.”

New revelations about Lois Lang’s transformation from homecoming queen to homeless killer provide excellent grist for substantive speculation, if not the basis for officially reopening the Deak case.

A standout college athlete with an M.A. from the University of Illinois, Lang married in the mid-’60s and took a job coaching the University of California-Santa Barbara women’s tennis and fencing teams. An old U.C.-Santa Barbara yearbook shows coach Lang standing tall in a team photo. It was around this time that she began losing her mind, seeing “fakes” all around her, strangers whom she accused of pretending to be family members, her husband and, at an open-casket funeral, her mother’s corpse.

In 1970, the university declined to renew her coaching contract. Lang and her husband soon divorced. Her life quickly became a blur. Lang complained of “amnesia” and said that her ex-husband’s business partner moved her into an apartment in Mountain View, Calif., where she lived on “grants” and “took flying lessons.” (Moffett Field Naval Base and NASA’s Ames Research Center are located there). She told psychiatrists in 1985 that this business partner, or his “fakes,” took her to Deak’s offices at 29 Broadway in 1971. She said that “friends” taught her marksmanship at firing ranges. In August 1975, records show that Lang was discovered naked and catatonic in a Santa Clara motel room. (Neither Lang’s ex-husband nor his “business partner” could be located. Lang, who is imprisoned at a federal facility two hours north of New York City, did not respond to interview requests.)

Police responding to the motel room took Lang to nearby Santa Clara Valley Medical Center. For the next month, she was put under the care of Dr. Frederick Melges, a psychiatrist associated with the Stanford Research Institute. One of Dr. Melges’ main areas of research: drug-aided hypnosis. A few years after Lang was put in Melges’ care, the New York Times exposed the Stanford Research Institute as a center for CIA research into “brain-washing” and “mind-control” experiments in which unwitting subjects were dosed with hallucinogenic drugs and subjected to hypnosis. Melges, who died in 1988, is today remembered in the field for his research on the relationship between perceptions of time and mental illness.

Congressional hearings subsequently uncovered a large network of top-secret CIA-funded psychological warfare programs grouped loosely under the project name MK-ULTRA. These programs today sound like absurd cloak-and-dagger relics of “Twilight Zone”-inflected Cold War hysteria. But the people running these programs, which continued until at least 1979, were often leading researchers backed by the U.S. government. Enormous resources were committed to the study of how human behavior might be controlled for the purpose of interrogation and the creation of “programmed” assassins and couriers. In a detailed roundup of MK-ULRA-related operations, Psychology Today explained that the CIA “conducted or sponsored at least 419 secret drug-testing projects” at “86 United States and Canadian hospitals, prisons, universities, and military installations,” and that “by the agency’s own admission, many [experimental subjects] were ‘unwitting’.”

The Stanford Research Institute received CIA funding, and Dr. Melges published work about using drugs and hypnosis to create “disassociative states,” i.e., induced schizophrenia. One of Melges’ partners on these experiments was a doctor named Leo E. Hollister, who first dosed Ken Kesey with LSD as part of an Army experiment in 1960. He later admitted to author John Marks that he conducted drug research for the CIA. Marks’ 1979 book, “The Search for the Manchurian Candidate,” contains numerous such revelations about other government researchers.

In other words, the doctor who cared for Lang in Santa Clara was a senior figure at one of the CIA’s top institutional grantees. He worked side-by-side with a self-identified CIA collaborator, and conducted research into the kind of drug-induced behavior modification that the agency is known to have funded.

Following her release from Melges’ care, Lang began a long period as a drifter, leaving behind a record typical of such a life: petty crimes, arrests, stints in and out of psychiatric hospitals. Her only known job was at the once famously mobbed-up Harrah’s casino on the Nevada-California border (where Frank Sinatra’s son was kidnapped in 1963). By the early 1980s, Lang drifted north to her birthplace and spent her last free years lurking around the University of Washington campus wearing a feathered Robin Hood cap. Occasionally she was arrested and sent to one of the nearby mental hospitals before making her way back again. A local police officer told the New York Times after her arrest in 1985 that Lang “usually had money,” despite roaming “the [university] campus in unkempt clothes, usually wearing a green felt Tyrolean-style hat.” Once the police found more than $800 in her possession.

As with Stanford, the university employed a military-linked behavioral psychiatrist, Dr. Donald Dudley, who later became infamous for carrying out experiments in behavior modification. Dudley taught there from the 1960s through the early 1990s, and also worked at nearby mental institutions where Lang was periodically committed. The landmark lawsuit that ended Dudley’s career revealed that Dudley’s hobby was taking patients brought to him for lesser mental illnesses, pumping them full of drugs, hypnotizing them, and trying to turn them into killers.

We know this thanks to a suit brought by the family of Stephen Drummond, who entered Dudley’s care in 1989 for autism treatment. He was returned to his family in 1992 suffering from severe catatonia. According to lawsuit testimony, Dudley shot Drummond up with sodium amytal and hypnotized him with the intention of “erasing” a portion of his brain and turning him into an assassin. When Drummond’s mother confronted Dudley, the mad scientist threatened to have her killed, claiming he worked for the CIA. Dudley was arrested soon after the confrontation in a local hotel where he had shacked up to “treat” a suicidal 15-year-old drifter. Dudley had given the boy sodium amytal and several other drugs, hypnotized him, and convinced him that he was part of a secret army of assassins. Police were called in when the boy threatened hotel staff with a .44 caliber handgun. Not long after, Dudley died in state custody and his estate was forced to pay the largest psychotherapy negligence lawsuit in history. During the trial, it emerged that Dudley had possibly subjected hundreds of victims to similar experiments. Lang was not mentioned.

* * *

If Lang was tapped to whack Nicholas Deak, she was part of a long tradition. In mobster literature, insane assassins are regular characters. “Nuts were used from time to time by certain people for certain matters,” explains Jimmy Hoffa’s former right-hand man, Frank “The Irishman” Sheeran, in his memoir, “I Heard You Paint Houses.” Chuck Giancana, brother of Chicago mob boss Sam Giancana, writes that he once heard his brother say that “picking a nutcase who was also a sharpshooter” to carry out an assassination was “as old as the Sicilian hills.”

An untraceable hit is the best hit, and the mind of a “nut” is all but untraceable. Hoffa associate Sheeran identified two high-profile examples in America. One took place during Hoffa’s trial in Nashville in 1962, when, during a break in the trial, a young paranoid-schizophrenic named William Swanson rushed into the courthouse and began firing at Hoffa. Hoffa’s attacker had been released from a California mental institution a few months before coming out to Nashville. “I had been struggling with something in me that told me I had to kill someone for over a year, but I didn’t know who,” Swanson told police after he was arrested. “Then a voice told me, ‘You have to kill Hoffa’ — it said it twice.” Hoffa had always assumed that rival mobsters had trained Swanson to take him out. A few years later, in 1971, New York’s top Mafia don, Joseph Colombo, was gunned down at an Italian-American pride rally by a 24-year-old African-American paranoid-schizophrenic, who was killed seconds later by someone in the crowd.

The Colombo assassination made headlines for months, and although everyone from the police chief down assumed mob involvement, the hit was never solved. Assassin Jerome Johnson was a black neo-Nazi as well as a practiced marksman and member of the NRA. He also thought he was God. The night before murdering Colombo, he arrived by bus from Cambridge, Mass., carrying a caged monkey. No one ever figured out whom Johnson visited in Cambridge, how he got his money, or why he had the monkey.

Lois Lang spoke to police and doctors on the day of her own arrival by bus. As during subsequent interviews with psychiatrists, she was incapable of offering more than sketchy and incoherent autobiographical information. She was hospitalized for eight years before a judge finally declared her fit to stand trial in 1993. The prosecution team found the case very odd — the D.A. reportedly still thinks about it — but didn’t spend much time delving into the motivations of the madwoman. Lang has been in Bedford Hills federal prison ever since. Her longtime attorney is deceased. She has grown a beard like a billy goat and ignores all interview requests. Her most recent parole interview was last August. Like every previous date, she failed to attend.

* * *

If the tossed-off human byproduct of a half-baked CIA assassin program was indeed recruited by one of many potential-suspect crime syndicates to kill Deak, how did it go down? Who provided Lang’s name to whom? Who helped her to buy a bus ticket to Florida via Tijuana? Who helped her buy a Saturday Night Special in Orlando and taught her to shoot?

Some of those loose ends may be tied up by opening government files. Since the 1980s, the CIA and Department of Defense have had to reveal thousands of pages of documents and settle scores of lawsuits filed by victims of various mind-control experiments. Recently a major class-action lawsuit was filed on behalf of over 7,000 veterans subjected to chemical and biological experiments at the 11th Circuit federal courts.

Arkadi Kuhlmann, the ING Direct CEO, may hold a few important leads. During our conversation, we told Kuhlmann that Lang was hospitalized under the supervision of at least one doctor with a documented interest in drug-induced hypnosis. He wasn’t at all surprised. “How does a woman like her actually handle a gun and get off two clean shots?” he asks. “That’s execution-style. It’s hard to function like an executioner one minute, but be loose around the edges. Unless you’re brainwashed like a robot.”

He then divulged a discovery he has kept to himself for nearly three decades. In Macau, Kuhlmann said, one of his investigators was tipped off about the potential involvement of two Argentinean gangsters in Deak’s killing. His team was able to trace the men’s movements in the months before the murders and discovered they had met with Lois Lang in Miami, not far from where Lang bought her murder weapon and took the bus to New York. “We’re absolutely certain they met with Lang,” Kuhlmann said.

What was this duo’s precise connection to Deak? And how did they come to meet Lois Lang?

Here Kuhlmann pauses for the first time.

“I know a few more things about them,” he said. “But this gets a little dicey. I don’t know how to play that game. I don’t want to be the next target.”

* * *

So let’s imagine that Lang was a product of a government-connected mind-control program. If jilted gangsters from Argentina and Macau used her to exact revenge, what could possibly connect them?

Allow us one more speculation rooted in the record.

As Deak’s banking empire was collapsing in December 1984, the depositors in Deak’s “non-bank” banking outfits — specifically the Connecticut-based Deak-Perera Wall Street and Deak-Perera International Banking Corporation — included numerous rich and shady Argentineans parking their “black” cash outside of Argentina. The country was in upheaval following the Falklands War debacle that led to the overthrow of Argentina’s quasi-fascist junta and the restoration of democracy. For decades, Argentina had been Latin America’s haven for some of the world’s most wanted, its capital city of Buenos Aires a European-flavored nexus for Nazi war criminals, global Mafiosi and Western spy services. The 1970s were the scene’s heyday, when Argentina’s junta coordinated “Operation Condor,” a regional crackdown carried out with the support of the CIA and allied dictatorships. Condor resulted in the deaths of tens of thousands of suspected leftists, including the car bombing in Washington, D.C., of Chile’s former ambassador.

This coziness continued into the early 1980s. Upon Reagan’s election, one of the first things Bill Casey did was farm out Argentina’s death squad commanders as trainers and commanders of anti-Sandinista death squads in Nicaragua, known as the contras. This arrangement worked fine until mid-1982, when Britain went to war with Argentina over the Falklands, and Reagan sided with Thatcher. In the wake of the war, the Argentine junta-mafia power structure collapsed. Suddenly a lot of very scary Argentineans with ties to the underworld and the CIA began to move their money safely out of Argentina, where Deak maintained a large foreign currency exchange business.

It’s all but certain that the bankruptcy of Nicholas Deak resulted in the burning of some of the CIA’s most ruthless, bloodstained allies of the Cold War. With his CIA ties and right-wing politics, Deak knew many of them personally. Kuhlmann recounted to us how shortly after he joined the firm, Deak brought him to a meeting with one of Chilean Gen. Augusto Pinochet’s top arms dealers. Such relationships combining financial and political networks offer a plausible scenario for how Deak’s bilked banking clients might have been able to tap a possible victim of CIA behavior modification experiments like Lois Lang. If any capital flight demographic in 1984 had deep ties to the CIA and their experts in torture, interrogation techniques and related “science,” it was Argentina’s fleeing junta-elite.

“Lang and the Argentineans — it’s like a jigsaw puzzle,” said Kuhlmann with a sigh. “You have to fill in the missing 30 percent. That doesn’t work in a court of law.”

Link to Original Article at Salon.com

No comments:

Post a Comment